what is a mold by any other name

introducing my thesis work on how chefs and food scientists are using mold to create new flavors

During my food science education, I was lucky enough to have spent time in Denmark for my Master’s thesis. Noma seemed to be one of the coolest places to work in 2015 as I got into food, and there was one word that I kept coming across in their and the Nordic Food Lab’s writings: koji.

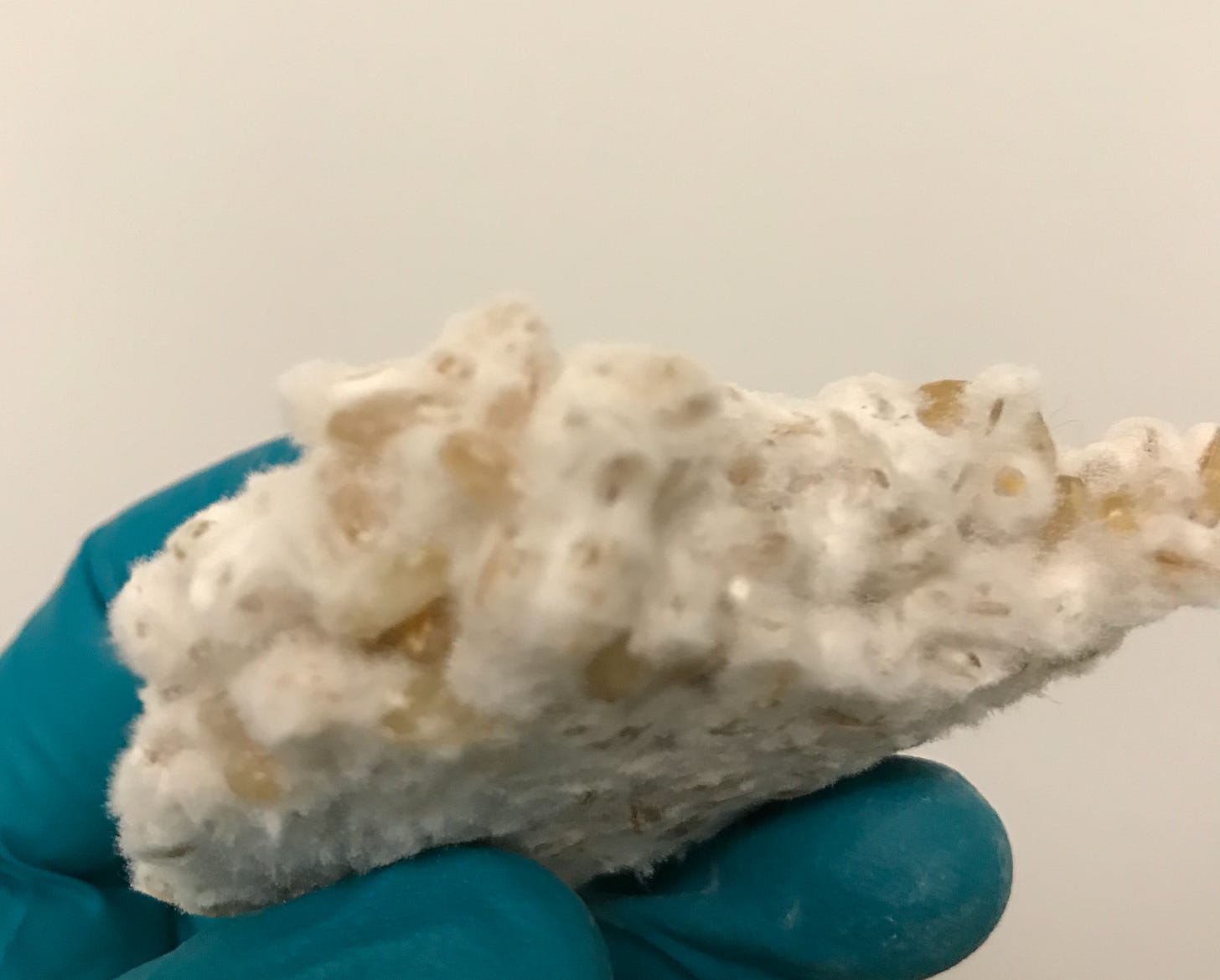

Like many Westerners at the time, I wasn’t really sure what this was. My interest in food really centered around fermentation and learning about the bacteria and fungi that made my favorite foods, but koji remained a mystery to me. There was something that I was missing about this furry grain of koji that I was resolute on learning more about, and this is the start of a series on my exploration into the world of flavorful molds.

It’s important to see where this wonder came from and how it’s come to enrapture the fine dining scene of the Nordics and then the world over.

history of koji

Before diving into its applications, let’s start with the basics.

What the hell is koji?

Koji is the basis for making many Japanese ferments and has gained increased popularity in Western kitchens in the past decade. Also called nurukgyun (누룩균) in Korean and qu (麹) in Mandarin, it helps develop the complex flavors of sake, shoyu (soy sauce), and miso. Kōji is a Japanese loanword in many Western languages and consists of two characters that separately would mean “rice flower.” The first documented Western writing of the word côji was in 1603 by a group of Portuguese Jesuits who were attempting to open trade with the island nation. At the time, this Portuguese portmanteau simply described a grain used to make sake, miso, and shoyu, but little else. Now, through rigorous study of koji, it has been found to be one of a variety of fungal species, the most prominent of which is Aspergillus oryzae, that has inoculated a starch source like rice, barley, and/or soy. Regardless of these findings, the English loanword koji can still confusingly refer to the following:

The fungal organism - there are a few Aspergillus species that can be used, like A. oryzae, A. kawachii, and Monascus purpureus.

The spores of that organism - we’ll get into this more in a minute, but these could be thought of as the “seeds” equivalent in plants.

The inoculated grain - this is the finished rice, barley, or sweet potato that has A. oryzae grown on it and is ready to use in cooking.

To make it easy, I’ll call out these three references more specifically as an organism, a spore, and an inoculated grain (e.g., rice koji). I realize that I’m pretty deep in the weeds here, trying to self-regulate my excitement about writing about my work.

cultivating enzymes

Much like our own bodies, A. oryzae and its cousins are living organisms that produce proteins to help break down food, like a rice grain, by making proteins to assist in the process. Let’s take a look at lactose intolerance as an example of how this works. When we’re young, we are able to produce a protein, more specifically an enzyme, called lactase that can break down lactose into sugar that we can digest. Over time, many folks lose this ability and develop an intolerance to lactose.

During the few days that it takes to grow A. oryzae, it goes through its own life cycle of producing two important classes of enzymes: proteases and amylases. Proteases break down protein into amino acids, while amylases break down starch that the organism can use for continued growth. Each species and its growing conditions produce different types and quantities of these proteases and amylases.

If you let these inoculated grains continue to grow, the fungus would mature and begin to produce spores that would continue its lineage. While it’s still in its peak growth, the rice koji is frozen, retaining the enzymes that it produced while the organism dies. Though it looks like we’re growing a fungus, we’re actually letting it create these enzymatic powerhouses as the building blocks for flavor-rich foods.

fine dining fixation

In 2009, Noma first started experimenting with koji in its own research and development kitchen, the Nordic Food Lab. Initially starting with miso, they used our fungal friend to break down steamed soybeans. Soybeans are rich in starches and proteins that the enzymes crave, so by mixing this finished rice koji, it starts a new process of fermentation. Oftentimes, the soybeans and rice grains are inoculated with the fungal spores at the same time rather than having two different fermentation stages, though.

This spawned a new fascination in the flavor creation of kitchens where I’ve seen high-end restaurants in Austin, New York, San Sebastián, and more look to harness this fungal technology to make drinks, sauces, desserts, and more. We’ll dive into certain dishes later, but using this fungus as a platform has shown Western dining that “fresh” food isn’t the only way to get the best out of an ingredient.

I am very happy I’ve come across your Substack. Was flicking through your post and i keep gasping. I want to read every single one! Weekend reading sorted