Growing up, my mom would make Betty Crocker brownies from a box and we always used vegetable oil (yes, I will lick the spoon still).

I never really thought about it at the time, but “vegetable oil” is an incredibly generic name. What vegetable is it even coming from? Turns out it’s typically soybean oil. I never considered that soybeans are truly seeds, since I really only had interacted with them as edamame or tofu. That’s such an odd distinction, but one I hadn’t really considered. For this small series, let’s define seed oils and vegetable oils.

All seed oils are vegetable oils, but not all vegetable oils are seed oils. Many of these seeds are grains, legumes or other staples that we consume in other forms, processed in a way that allows us to extract their oil. This is distinct from olive oil, where the oil comes from the fruit itself, not the pit (seed) inside. For those who aren’t fans of olives with pits, avocado oil works similarly: the fat is removed from the fruit, and the pit or seed is discarded.

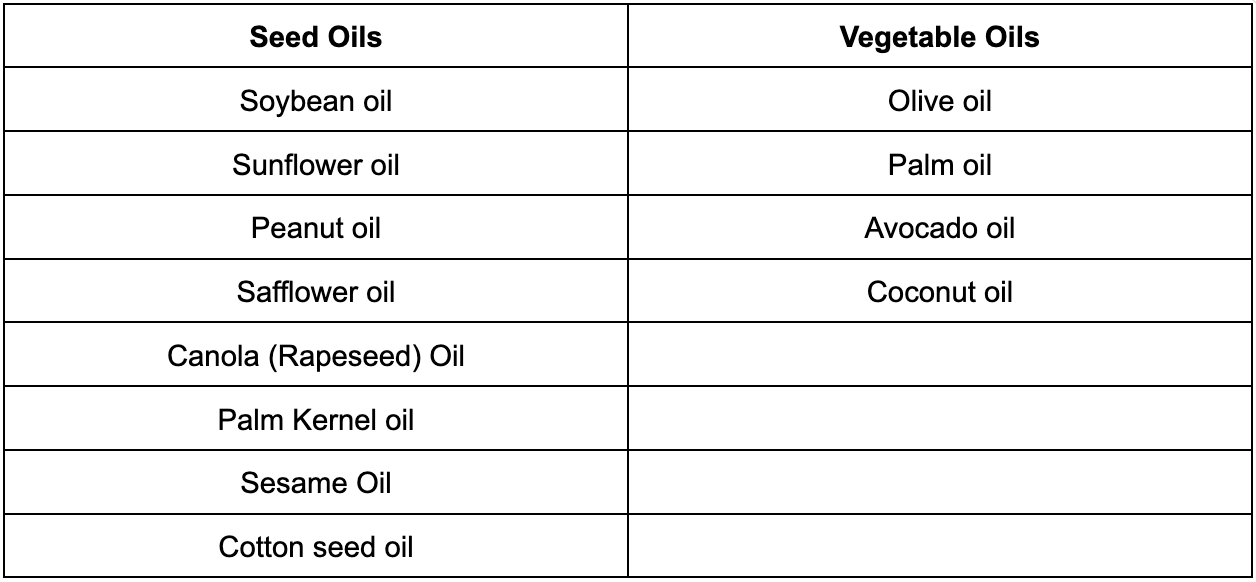

Let’s look at a quick list of other seed and vegetable oils:

Seed oils are often praised for their high smoke points, neutral taste, and almost non-existent aroma. That’s not true for all, as I definitely seek out sesame oil for its flavor and aroma. Regardless, when I even try to compare either list to a prized possession in my home, olive oil, I am at a loss of words. Olive oil is such a gift and finishing oils are as exciting (often times more, these days) than a fine bottle of wine.

Most baking recipes, as well as pan-frying or deep-frying applications, use seed oils nowadays. This past summer, we made those same Betty Crocker brownies with my fianceé’s family while on vacation, but we used olive oil and they weren’t exactly a hit. Culinarily, seed oils aren’t always swappable, but how did they get big enough that Presidential nominees turned Head of Health and Human Services Department home in on them?

where did seed oils come from?

The history of seed oils is closely tied to the Industrial Revolution and the evolution of food manufacturing. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, technological advancements made it possible to extract oil from seeds on a large scale. This innovation was driven by the need for affordable cooking fats as animal fats, like lard and butter, were relatively expensive and limited in supply.

One of the earliest commercial seed oils was cottonseed oil, a byproduct of the cotton industry. Previously considered waste, cottonseeds were transformed into a valuable resource through refining processes. In 1911, Procter & Gamble capitalized on new cottonseed oil production by creating products such as Crisco, which became a staple in American households. They even developed a new process, called hydrogenation, to modify the naturally liquid cottonseed oil into a solid at room temperature.

The 20th century saw a significant rise in the popularity of other seed oils like soybean, corn, and rapeseed canola oil. This shift was driven by the 1950’s bedrock research that encouraged reducing saturated fat intake in favor of polyunsaturated fats found in seed oils. When we think about the Hierarchy of Needs for Food System Change series, it seems like these oils are an absolute knockout: flavorless, aroma-free, neutral appearance, versatile in countless applications, cheaper, nutritive (...or not?), and upcycling a waste stream. Between great marketing and great products, they become a staple in all kitchens. However, it took decades of experimentation to develop the processes that make seed oils as useful as they are today. Let’s explore how this transformation happens.

crush ‘em up

Going from a sunflower seed to sunflower oil can take a few different forms, and all of them entail pulverizing the living hell out of it.

mechanical extraction

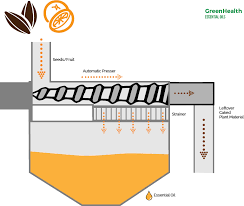

The least refined version of any oil will be broken up, pressed, filtered and packaged right away. An expeller press is the most common way, which is a large screw that squeezes sunflowers to extract the oil while separating the remaining fiber and proteins.. Expeller pressing is decently efficient - pulling out 65-80% of all the oil from the seed, and the hotter this process is done, the more oil can be pulled out.

Heating the press during extraction reduces the oils viscosity, making it easier to separate from these solid seed components. Importantly, this method of extraction retains the flavor, aroma and nutritive aspects of the seed (yes, the seeds are actually healthy). Specifically, they retain vitamin E, polyphenols and a family of compounds called phytosterols. These compounds are the plant-equivalent of cholesterol, and the main ones in sunflowers have anti-inflammatory, LDL cholesterol-lowering, and joint health benefits. Mechanical extraction actually allows for a fuller expression of the gastronomical and dietary benefits of the seed, especially compared to the far more common way of oil separation.

solvent extraction

When people think of "seed oils" in the context of news articles and podcasts du jour, solvent-extracted, or refined, oils are actually what come to mind. Unless an oil is explicitly labeled with terms like “extra virgin” or “cold-pressed,” it has likely been refined through this method, or parts of this method.

Sunflower seeds are broken up and soaked in hexane, a very fat-soluble solvent, and then filtered from the rest of the solid seed components. Think of it like making a french press of coffee, but it smells more of gasoline and your coffee grounds are the sunflower seeds. This big sunflower-hydrocarbon french press is incredibly efficient, extracting up to 98% of the oil from the seeds.

Afterward, the hexane is evaporated off, leaving behind just the oil which goes through further refining. A series of processes make up refining, but the bleaching and deodorization steps are typically the ones that (likely warranted) catch the most flak. High-temperature, high-vacuum steam distillation removes any aromas or off color, and scrapes away anything that gives the oil the essence of its sunflower-y past.

This optimization for efficiency of removing the oil is at the cost of the nutrient density, flavor and aroma of the oil itself. Virtually all of the polyphenols, phytosterol and oil-soluble vitamins are gone and you're left with a straw-yellow oil with a higher smoke point. Thankfully, seed oils are definitely the only type of oil we expose to this harshness, and we never have to worry about our precious vegetable oils being tainted with gas components and icky distillation techniques that just won’t do.

good thing we don’t do that with vegetable oils…

…not

Remember how I said if there isn’t some qualifier on the front label of oils, like extra virgin, they’re almost certainly refined. That logic extends to avocado, olive and coconut oils. For this section, I’m going to pick on avocado oils because they’ve been touted as a panacea for the evils of seed oils.

Ever wonder why avocado oil doesn’t taste like avocados? Recall that the deodorization step in the refining process takes out any of the defining flavors and aromas of its origin. Most avocado oil isn’t solvent extracted, but cold-pressed, which is a Mom-and-Pop market phrase for centrifuge filter.

Regardless of the extraction type, you can still refine avocado oil, and almost all of the avocado oil sold in grocery stores, and virtually all of it in CPG products likely is.

To make matters more confusing, UC Davis published research in 2020 looking at 24 avocado oils brands and found only 2 of them were high quality and hadn’t gone rancid. Even a few of them were found to likely be soybean oil! Without stricter regulation, your precious green gold oil can be adulterated anyway, which begs deeper questions of both the FDA and consumers alike.

MAHA and RFK Jr. and the seed oil revolt

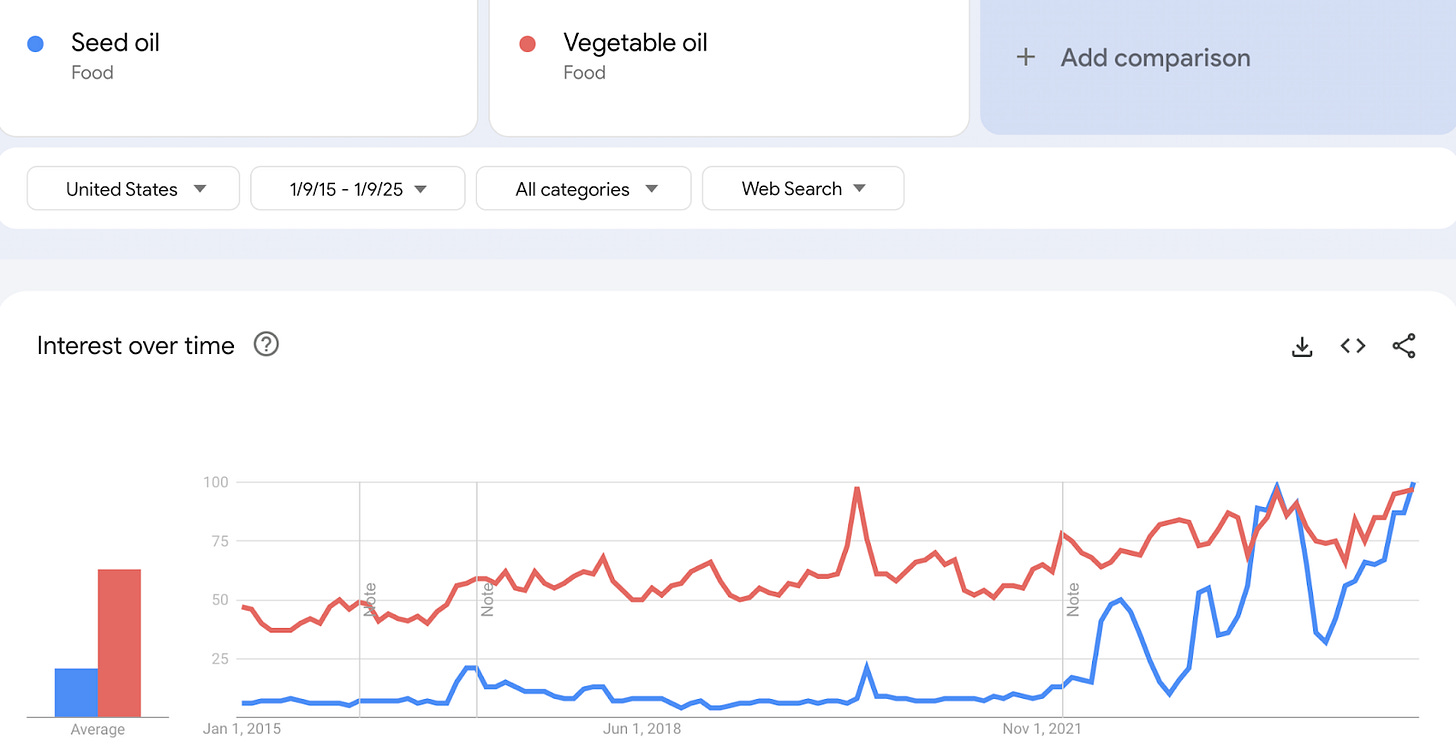

With the new administration coming in and looking to cut or reform everything in sight, you probably have heard about Robert Kennedy’s War on Seed Oils. Though, if you look at Google Trends, no one other than commodity traders differentiated seed oils much from vegetable oils until 2021.

RFK has given a megaphone to the simmering discussion in health circles about seed oils. Since at 2022, I’ve heard thought leaders show hosts talk about these pesky carry overs of our broken food system. These come from hard-hitting n=1 studies where they cut them out, cut the bullshit, and cut down unproductivity and inflammation. So clearly the data is in.

Saying diet is personal is an overstatement and everyone should experiment to find out what makes them feel best day-to-day. The best aspect of these articles and episodes is that they inspire folks to go on their own personal journey of understanding their body and how the food they eat affects them. I’d love for folks to go a level deeper and sort out why or how seed oils could be bad for you, but knowing that I don’t always do that myself, I couldn’t expect any of you to either.

In the seed oils discussion, I still want to touch on linoleic acid, omega-6 vs. omega-3 fatty acids, and the trans fat genesis debate. I want to peer into the depths of each of these and see what we find. If there is something to be aware of, I also want to make sure that we’re not sweating it over the type of oil in our brownies.

All I ask is that we look at how all commodity oils are made and ask ourselves what we’re actually uncomfortable with: the seed or the process?

I finally got round to this on my reading list! First off - LOVE the graphics! Secondly, vegetable oils has always been such a grey area for me, because 'vegetable' is so elusive hahaha. I still struggle to figure out how to buy "good quality" vegetable oil for making things like vinaigrettes or dressings. More-so because what does that mean... I'm guessing from what you've said here, cold-pressed/refined would be the way, and also realising what the label 'vegetable oil' actually means!! This has really helped!